Jens Bjørneboe

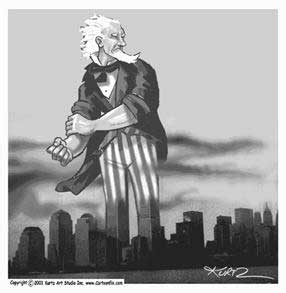

The Fear of America Within Us

(Excerpts)

Translated by Esther Greenleaf Mürer

Jens Bjørneboe, "Frykten for Amerika i Oss". Originally published in Spektrum, 1952. Norge, mitt Norge (Oslo: Pax, 1968); Samlede Essays: Politikk (Oslo, Pax, 1996), 12-21. ©1968, 1996 by Pax Forlag A/S. English translation ©1999 by Esther Greenleaf Mürer.

We live between two poles of dread. One of them lies up in plain daylight; it is the fear of Russia and of many things whose nature we know: hunger, bombs, mass transports and concentration camps. That is an officially accepted, recognized dread.

The other pole lies deep down in our unconscious and in the dark. And its emanations are noticed only by those who are sufficiently sensitive or young. It is the terror of America and of something no one can rightly identify. It can take the form of modernistic poetry or of an ordinary nervous breakdown. Or it can be camouflaged and made operational by an arsenal of communist slogans: warmongering, capitalism, imperialism, etc. But there is no getting rid of it. For the dread of America is the fear of an inner state, of America within us.

In Americanism's footsteps follows an attitude which impoverishes life and makes death meaningless. Death is an uninvited guest, whose arrival cannot be forestalled with the help of refrigerators and illustrated magazines. Life, on the other hand - oh, we know what life is: it is canned pineapple.

The media chosen by the U.S.A. to represent it in Europe continually proclaim that the secret of life is solved: the radio-refrigerator is what humanity was waiting for. And furthermore the new Buick model will have 170 horsepower. The theme runs like a red thread through everything we hear from America: the great democracy is inhabited by humans of a new kind, by splendid, half-mechanical giant babies who live on canned tomato juice and synthetic vitamins. In America they add artificial sweetener and vanilla flavoring to the chocolate. Those super-red apples have long been a well-known product of American culture. But last Christmas I came across some oranges of particularly tempting, chrome-yellow splendor. When I pressed the first one, the color came off on my fingers. And sure enough: on the rind was stamped "Color added." The color was as false as a technicolor film. For me that was a novelty at the time.

While Russia offers us vistas of hell on earth here and now, the U.S.A. can treat us to paradise on earth. But the thing about this paradise is that when you've lived there for a while, the apples and the oranges need makeup in order to be noticeable. Life must be colorized.

America's weakness for the artificial is something quite different from a simple lack of culture. It is a sickness, a kind of premature aging. The paradise of American civilization has produced the Rockefeller physiognomy, and therewith a peculiar, ambiguous symbol: the fetus and the old man in one. It is the unborn and the dying, and, be it noted, something is dying which does not want to die. The dread of death is companion to the appetite for life.

The fear of death is the great night casting its shadow over the American paradise. Thomas Wolfe has described it unforgettably. And the future's first social task must then be to produce a race of humans too dull to know about death.

Many feel instinctively that this is a very high price to pay for colored oranges.

It may be appropriate here to recall a burial custom which has long been on the rise in the United States. It is a variation on lying in state which has a very strange effect on unprepared Europeans.

Before cremation the corpse is taken under treatment by skilled beauticians. He or she is made up and treated with injections to restore a life-like roundness and color, the hair is arranged to look as much as possible as it would after a car trip or before a party, the eyes are opened and given a sheen, and the deceased is dressed in party clothes or a sports outfit, according to the person's taste and character. The corpse is then set in its accustomed place in the family living room, with a glass, an apple or a cigarette in its hand, its favorite phonograph records are played, its picture taken. Then follows the funeral.

This - and much else - has not come about by itself. All such phenomena are unconscious reflections of the American view of life. Whether one is putting makeup on corpses or apples is immaterial. When a people wash themselves so much outwardly, says Thomas Wolfe, inwardly they must be very slovenly indeed. Washing promotes health and well-being, washing prolongs life. The healthier you are and the longer you live, the more pleasure you can squeeze out of the material paradise. Add artificial pineapple flavor to the pineapple and smear pink plastic color over it all; for under us, behind us, off the dance floor, outside the neon light, the Meaningless One lies in wait! Death, the only true snake in Eden!

Our participation in America's view of life I call America within us. The heavenly, new America, independent of time and space.

The earthly America is a place where thinking and feeling human beings are worse off than anywhere else in the world. You don't have to be a specialist in American literature to arrive at that idea. But then are the ones over there who are in fact the wretched, the ones who are not pictured on the magazine covers? Since it is still true on earth that man is man's joy, this will be the first and weightiest question we pose to America:

Where are our American brothers?

Among my first impressions were meetings with a steady stream of North Americans. That was in the late twenties and early thirties. It was after the Wall Street crash, and long before the days of hard currency. And people in Europe did not yet regard the Americans as roaming wads of dollars. They were still human beings in our eyes, people you could talk with without ulterior motives and without being suspected of ulterior motives. You could buy American cigarettes at all Norwegian tobacconists, and we didn't yet have the poor-and-rich complexes which plague us today ....

Back then too the U.S. was the land of wealth and gold. We knew that very well. But we also knew that people had to work for it over there, work so hard that at a young age they needed both gold teeth and gold-rimmed glasses to be able to see and chew. And it never occurred to anyone to begrudge them their wealth. The poor fellows had slaved hard enough for it, while we back home in the old country sat around reading books and fishing whiting, and couldn't even be bothered to convert our waterfalls into profitable power stations. It never occurred to anyone that the Americans were there to get rich on. And if they had inch-thick gold chains over their bellies, if they bragged about their cars and their houses, they weren't trying to say "Here you see a boy who has money!" They were showing us that they were people who had worked more and harder than we could conceive of. We really looked at them without envy - they were brothers and fellow human beings, and if we laughed at them, the laughter was without malice.

Today it is utterly different.

We have swallowed so much of America's view of life that we can no longer see the people over there. There are views of life which unite and views of life which divide. One can never establish a relationship to a person one hopes to get rich on.

The first foreign country I visited was the U.S.A. When I went ashore on the pier in Brooklyn, I knew neither Denmark nor Sweden.

On the voyage over I had become friends with an American boy of my own age.... Since he was from the Midwest, we parted in New York, and since then we haven't seen each other. It didn't occur to us that he should finance me in any way.

Today the problem would have arisen. The awareness of class difference would continually be lurking in the background. For five of the years which have elapsed since that time, we in Europe ate sardines with heads and intestines and tail fins. We collected cigarette butts and did many other strange things. And wegained the fundamental insight that this is not what it's about.

Fellow feeling is what it's about: To be able to be a human being among human beings.

Until further notice, a few bars of a communist battle song have more allure for the soul than a whole Atlantic ocean full of canned pineapple. Aren't there people on the other side of the ocean too who are willing to leave shop and field in order to devote themselves to the quest for the Holy Grail?

It looks as if America has begun to secrete a new type of American, a new and un-American being.... The young Americans who bum around Europe today are spare parts who don't fit into the big U.S. machine. They are of a different make. They are often poor, and have that strange homelessness in their eyes which shows that here is a whole generation, a whole new type of people on the move. They are no longer "innocents abroad" - they are not abroad, because they have no homeland. You find them especially in the old cultural centers, and they voluntarily renounce all that America has to offer them if they can just starve through another winter in Florence, Rome or Paris. The more past a city has, the more certain it is to suck to itself people who are starved by a lack of history. The tragic thing is that these young Knights of the Grail from a new America are looking back to Germany, Italy and France, to the lands of their grandparents, at a time when the remains of European culture are in the process of being forgotten. The historyless are looking for their past in a continent which itself is on the verge of becoming ahistoric.

American birds of passage of the last generation likewise sought milder latitudes in Europe. They sought culture and spiritual tradition, and met a generation of Europeans who had grown tired of both. A tired, critical and revolutionary intelligence met the pilgrims by recommending primitivism. And this (in part) highly gifted generation from the time after the First World War turned out to have a lower cultural potency than any of its bourgeois predecessors. For all who have looked with admiration on the great revolutionaries from the period between the wars, it is a bitter fact to swallow: The rebellion against the bourgeois tradition has resulted in a painful banalization of the cultural life.

It is almost impossible to write about this without resorting to facile formulas. But it is nonetheless certain that the vast wave of longing for brotherhood, the wave which socialism and radicalism swallowed up, was in reality the longing for a new primitive Christianity. It is just as certain as the fact that a Europe without two thousand years of Christianity could never have invented anything like socialism. Had socialism been mindful of its ancestry, it would have been able to work against the churches - with regret, but without throwing Christianity out with the bathwater. Clarity that Christianity is a religion of brotherhood - and the direct opposite of the conservative principle - could have given rise to something like a gigantic Quaker movement, a movement oriented toward both earth and heaven. A writer like Ignazio Silone can be mentioned as representing such a socialism. The difficulty, of course, is that social compassion demands a type of Christianity which can be taken seriously to an unheard-of degree.

The Americans who looked to Europe in the first half of this century did not achieve firm contact with what they were seeking. The cultural generation which received them was by no means convinced of the worth of the European heritage, and completely abstained from transmitting it. The young America resembles a younger brother who, returning home to the parental homestead to claim his inheritance, is told that he shouldn't have bothered; it's nothing but worthless old junk.

Today it may be possible for us to take another look at that inheritance before we irrevocably burn it up. Perhaps our spiritual storerooms will turn out to contain treasures which we literally hadn't dreamed of. We have gained a distance which may make possible a new and fresh evaluation of the whole European idea.

Europe is the land of Christendom. European culture is not a Christian culture; it is the Christian culture. Every fruit which the last 1800 years have borne on European soil was of Christian descent.

What we fear today from east and west is nothing else than the extinction of brotherhood. And it lies in Europe's nature that we must regard this as the worst of all evils: It would mean Christianity's complete eradication from the earth. A world without brotherhood, for the European, would mean a world without aim or meaning. It gives a perspective of a boundless sadness and emptiness.

The idea of brotherhood lies so deep in European culture that we can find it in all shades. It is our picture of the world. And if one cannot see the parallelism in such different formulations as Francis of Assisi's "brother ass" / "brother sparrow" / "brother wolf" and Darwin's doctrine of the origin of species, then one is either a religious or a scientific dogmatist.

Freedom and equality are thoughts which would never have been thought had the idea of brotherhood not provided fertile soil. But once they are there, they can forget their origin and take on lives of their own. Europe embraced the holy, threefold motto: liberty, equality, fraternity. The West chose freedom. The East chose equality. But freedom without brotherhood is the economic and social law of the jungle. Without brotherhood freedom becomes divorced from equality.

And in the East: Equality without brotherhood becomes equality without freedom. The three concepts are inextricably interwoven.

It is strange - yes, more than strange - that the "atheistic" French Revolution chose a slogan which is a direct paraphrase of Christendom's concept of the Trinity (Before the Father we are equal, before the Spirit we are free, and before the Son we are brothers.)

The radical intelligentsia rejected Christianity with unforgivable irresponsibility. But they did so with the best intentions. They disassociated themselves from it without investigating what it was; but it would be wrong to believe that Christianity can be justified with the same ease. Perhaps the radicals themselves have provided the best springboard for what is required: They have removed conscious Christianity to such a great distance that we will be able to regard it with new eyes. They have broken the line of succession, and a Christianity which is not handed down will have fulfilled the first precondition for becoming a primitive Christianity. And when it is understood that brotherhood is our essential plumbline for distinguishing between good and evil, that everything which in European eyes serves brotherhood partakes of the good, and whatever does not in our eyes serve brotherhood is of evil, and that this is so because we are imbued with Christianity to the bottom of our souls, and because this Christianity has fully-realized brotherhood as its inmost and deepest secret - then the day is not far away when Europe can assume its appointed position as the Land of Brotherhood - along with the Land of Freedom and the Land of Equality.

Once it has become clear to us that we experience unbrotherliness - exploiting and oppressing others, denouncing others as heretics, greed, lust for power, racial hatred - as the basest of all sins precisely because they are anti-Christian, then we will be able to meet our American brothers in a common quest for the Holy Grail. And we will be able to mediate Europe to them, hand over their inheritance without casting doubt on its worth. The days of cultural pessimism will be past, quite simply because our Christian European culture is our highest and most cherished possession - what we at the bottom of our hearts have always loved above all else. One may think what one will about Christianity, but it cannot be nullified; it is sown in us and has been growing in our unconscious for two thousand years, it has become blood and bones, sight and hearing, facial expressions and body language. And if equality, liberty and fraternity should ever be eradicated from the face of the earth, they will still live on in our hearts - as the unquenchable longing for brotherhood. We can mock Christianity, scoff at it, detest it; the day we pull the veil off it, we will recognize the beloved of our youth, our only love.

More Jens Bjørneboe in English

Click to join anthroposophy_tomorrow

Visit the Rudolf Steiner electronic library